What Is the Record High Reading for the Edwards Aquifer

| Edwards Aquifer | |

|---|---|

Downstream from the headwaters of the San Marcos River | |

| Location | Edwards Plateau, Texas Hill Country, Texas, The states |

| Expanse | iii,237 km2 (1,250 sq mi) |

| Geology | Limestone karst[1] |

| Website | Edwards Aquifer Website |

Edwards and Trinity Aquifers Map

The Edwards Aquifer is one of the nigh prolific artesian aquifers in the globe. Located on the eastern edge of the Edwards Plateau in the U.Due south. state of Texas, it is the source of drinking water for two 1000000 people, and is the primary water supply for agronomics and industry in the aquifer's region. Additionally, the Edwards Aquifer feeds the Comal and San Marcos springs, provides springflow for recreational and downstream uses in the Nueces, San Antonio, Guadalupe, and San Marcos river basins, and is home to several unique and endangered species.

Basin characteristics [edit]

Geography [edit]

Located in Southward Central Texas, the Edwards Aquifer encompasses an area of approximately 4,350 square miles (11,300 kmtwo) that extends into parts of 11 counties.[2] The aquifer's boundaries begin at the groundwater divide in Kinney County, East of Brackettville, and extend Eastward through the San Antonio area and then Northeast where the aquifer boundary ends at the Leon River in Bell County.[3] The aquifer is hydrologically separated into the Austin and San Antonio regions by a groundwater carve up near the town of Kyle in Hays County.[2]

The total surface area of the aquifer forms roughly the shape of a slight upwardly curve and approximately measures 160 miles east to west at its furthermost boundaries and 80 miles due north to due south at its widest section.[four] The aquifer is geographically divided into four distinct regions: the total drainage area, recharge zone, artesian zone, and saline zone. These zones run east to due west, with the drainage area forming the northernmost portion of the aquifer and the saline zone forming the southernmost portion. The artesian zone intersects the saline zone to the south and west at the fresh h2o - saline h2o purlieus (FW-SW).[5]

The aquifer's recharge zone,[vi] where surface water enters the aquifer, follows the Balcones Fault line, from Brackettville (roughly along U.S. Highway 90), through San Antonio, and north to Austin along but a few miles west of Interstate 35. On certain stretches of highway in Austin and San Antonio, signs signal that the commuter is entering or leaving the recharge zone, as the zone'south easternmost edge sits below heavy urban and suburban development.

Its drainage area, where water is transported near the surface to the recharge zone, extends about twoscore miles (64 km) north of the recharge zone at the west end, and tapers to end at a point in the east.

The artesian zone,[7] where water springs from wells naturally due to the higher height of the recharge zone, extends 10–twenty miles (sixteen–32 km) southward on the west end to simply a few miles s on the east end. Across the eastern half of the aquifer, the recharge and artesian zones occupy common area.

Geology [edit]

Approximately 70 meg years ago, activity of tectonic plates caused a revival of the Rocky Mountains. As these tectonic processes were occurring, millions of tons of sediments were deposited by alluvial and fluvial processes beyond Texas. The tremendous weight of these sediments resulted in faulting betwixt the Edwards Plateau and the Gulf. The chief geologic unit, known as the Edwards Limestone, is tilted down toward the south and east and is overlain by younger limestone layers as well as several thousand feet of sediments. The Edwards Aquifer is a group of limestones and is considered a highly heterogenic aquifer.[8] Three stratigraphic columns across the San Antonio area represent the Edwards Aquifer. These stratigraphic units are known as the Maverick Basin. the Devils River Trend, and the San Marcos Platform.[ix]

The Maverick Basin portion of the Edwards Aquifer consists of the West Nueces, McKnight, and Salmon Peak Formations. The Devils River Trend unit of the Edwards Aquifer is composed by and large of Devils River Limestone with a thickness of approximately 550 feet. The third unit of measurement of the Edwards Aquifer, the San Marco Platform, consists of the Kainer, Person, and Georgetown Formations.[9]

Karst formation from Segovia, Espana.

Hydrogeology [edit]

The Edwards Aquifer is a highly productive karst aquifer made upwards of Edwards Group limestones.[ten] The Edwards limestone is variable in hydrologic graphic symbol, simply is generally highly porous and permeable, which makes it able to hold and move a lot of water. The limestone is broken past faults and joints. H2o flows through these fractures and continues to deliquesce the limestone, creating larger and larger pore spaces over time. Some units as well store water in eroded fossil burrows that formed through the burrowing activeness of worms and crustaceans at the seafloor. The effective porosity, or the amount of h2o that is capable of being recovered, of the Edwards aquifer is estimated to be almost five%.[xi] The aquifer ranges in thickness from about 300 to 700 feet (100 – 200 meters).

Master Barton Leap in Austin, Texas, a prominent fracture (visible here) in limestone rock. Through this artesian karst spring water emerges to the surface from the karstic Edwards Aquifer. This spring is situated most the diving lath in Barton Springs Puddle. Photo provided past US Geological Survey.

Dissimilar sand and gravel aquifers that store water in very small pore spaces, karst aquifers shop h2o in large pockets or caverns, forming underground "rivers" and "lakes".[12] The rate at which groundwater moves through these conduits tin can vary tremendously. In the Edwards Aquifer some h2o may barely move, while in other areas h2o may travel miles (thousands of meters) in a single 24-hour interval. On boilerplate, the Edwards aquifer has been modeled with a transmissivity of nigh 100 ft2/day (9.29 m2/mean solar day).[11]

In the south, the Edwards Aquifer dips beneath the lowland plains of the gulf declension. This surface area south of the recharge zone is referred to as the Artesian Zone, where the water is held under pressure by depression permeability layers, and can flow to the surface without the assistance of pumps through openings like springs and artesian wells.

Climate [edit]

The Edwards aquifer underlies a portion of the Edwards Plateau[13] thus the climate of the Edwards Plateau can be used to depict the climate in the aquifer's region. The eastern portion of the Aquifer falls in a Boiling subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa or Cwa), while the western has a semi-arid steppe climate (BSk and BSh) The average annual temperature on the Edwards Plateau is 66 degrees Fahrenheit and the average almanac atmospheric precipitation amounts to 25.24 inches.[14] The temperatures vary by season with the lowest boilerplate temperature occurring in Jan, l degrees Fahrenheit, and the highest temperature occurring in July or August, nearing 85 degrees Fahrenheit for both months.[14] Conversely, Jan is the month with the lowest atmospheric precipitation, averaging ane inch, while May and September average the nearly, iii inches.[xiv] The proximity of the Edwards Plateau to the Gulf of Mexico and its location in the centre latitudes creates variation in the weather patterns experienced between different years, seasons, and months.[xiv]

Water quality [edit]

Approximately ane.v million people obtain their drinking h2o from the Edwards Aquifer. At present, the h2o quality of the aquifer has satisfied drinking h2o standards and at that place have been no significant issues with pollution contamination.[15] [sixteen] Regular water quality testing through the USGS NAWQA Plan occurred between 1996 and 2006. On a yearly basis, ions, metals, nutrients, bacteria, pesticides, VOCs, and synthesized chemicals remained below the EPA's published Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs).[17] [18] [19] [20] Dissolved nitrates (NO3) are detected throughout the unabridged aquifer at concentrations that exceeded the national background levels3, just that are well beneath the MCL (10 mg/Fifty).[16] These nitrates may exist the result of agricultural runoff that enters the aquifer through its recharge zone.[18]

Due to the karst hydrogeology of the Edwards Aquifer, chemicals that enter the system accept the potential to apace travel through the aquifer and contaminate downwards-gradient water sources in a brusque period of time (hours to days).[21] Aquifers can be hands contaminated when pollutants enter the recharge zone. Because of this vulnerability to contamination, organizations have formed to protect the Edward'south Aquifer recharge zones.[22] Anthropogenically sourced pollutants (pesticides, VOCs, and synthetically derived compounds) can be found within the Edwards Aquifer at minuscule levels.[18]

Ecology [edit]

The Edwards Aquifer supports a wide multifariousness of organisms, and several owned species. The ecosystem is 1 of the near diverse subterranean aquatic ecosystems in the world.[23] The widemouth blindcat (Satan eurystomus),[23] a unique species of blind catfish, has been pumped out of wells nigh 610 meters deep along the FW-SW boundary.[24] However, all aquatic-dependent plants and wildlife in the Edwards Plateau expanse rely on the aquifer to back up essential components of their habitats. Currently, the terrain is dominated by oak – juniper parks.[25] The dominant woody establish on the Edwards Plateau is Ashe juniper (Juniperus ashei).[26]

Edwards Aquifer is domicile to a large number of invertebrate species, forty of which have been described.[25] The most diverse groups are the prosobranch gastropods and amphipod crustaceans. The Edwards Aquifer has the highest recorded diversity of stygobites in the world.[27] In the U.s., but the creature of the Edwards Aquifer of Texas has a significant component of marine-derived species. Of the major karst regions in the Usa, information technology is the only one with a significant marine component.[28] Of the 64 stygobionts known from the Edwards Aquifer, 17 are marine relics.[29]

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) consider the Comal and San Marcos Springs ecosystems to have ane of the greatest known diversities of organisms of any aquatic ecosystem in the Southwestern United States.[thirty] This is due in office to the constant nature of the temperature and catamenia of the aquifer waters that have created unique ecosystems supporting a high degree of endemism.[31] The Edwards Aquifer is the sole environment for the rare Barton Springs salamander (Eurycea sosorum), which is a federally listed endangered species.[32] At Comal and San Marcos Springs, their openings and in the rivers and lakes originating from the springs, one threatened and seven endangered species have been listed by USFWS under the Endangered Species Human activity of 1973. The San Marcos salamander (Eurycea nana) is listed as threatened. The San Marcos gambusia (Gambusia georgei), Texas wild rice (Zizania texana), fountain darter (Etheostoma fonticola), Texas blind salamander (Typhlomolge rathbuni), Comal Springs riffle beetle (Heterelmis comalensis), Comal Springs dryopid protrude (Stygoparnus comalensis), and Peck's cave amphipod (Stygobromus pecki) are listed as endangered.

Land use [edit]

State apply through the region atop the Edwards aquifer varies betwixt rangeland, agricultural and residential/urban. The northern portion is primarily rangelands and contains about of the streams feeding the recharge zone.[33] Until the late 1990s much of the state expanse that recharged the aquifer was undeveloped rangeland, but since that fourth dimension it has undergone a meaning increment in evolution.[34] From 1996 to 1998 residential country utilise increased 9 percent in the Edwards aquifer recharge zone; even so, 72 percentage remains undeveloped.[35] The region atop the Edwards aquifer continues to increase in population today. In 2012 the US Demography Bureau noted 4 counties located within the Edwards Region; Kendal, Comal, Hays and Travis were amid the fastest growing in the nation, all with growth rates between 25 and l percent.[36] An estimated 4.6 percentage of the recharge zone is at present covered with impervious surfaces which decrease aquifer recharge and can negatively affect water quality.[35]

Almost all of agricultural lands and a big portion of San Antonio overlie the bars portion of the aquifer (Barker 1996). In an effort to preserve undeveloped state the city of San Antonio passed the Edwards Aquifer Protection Programme in 2000 (renewed in 2005, 2010 and 2015). The plan allows the city to purchase conservation easements for land in Bexar, Medina and Uvalde counties. The landowners retain and upon understanding the landowners cannot separate or develop the state and are paid twoscore-45% of market value for the easement. The plan has over 130,000 acres enrolled.[37]

Demographics [edit]

More than 1.7 million people rely on water from the Edwards Aquifer for municipal, industrial and daily use.[38] I of the major cities on the aquifer is San Antonio, America's 7th largest metropolis, with a population of over 1 million. San Antonio is heavily dependent on the Edwards Aquifer for their municipal, industrial and daily utilize.[36] Another major city on the aquifer is Austin. More than 50,000 people in the city of Austin (half-dozen% of Austin's population) rely on the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer.[38]

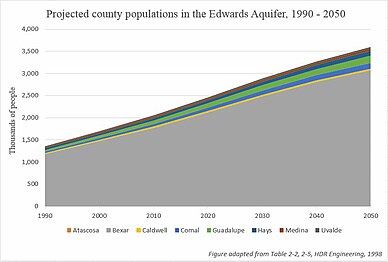

Between 1990 and 2015, the population increased past two thirds, at this rate, the population of the basin will be doubled in 2050. The population across the counties have approximately the same growth rate of 10% per year. However, Comal and Guadalupe have a greater growth rate of more than than 25% per yr. This will increase the number of people relying on the aquifer for daily water use.

Economic system [edit]

The Edwards Aquifer underlies 38 counties in South and Western Texas.[39] West Texas is regionally defined by jobs in the oil and gas industries, just is as well dwelling house to mining support, agriculture, and transportation support, amid other sectors.[40] South Texas is regionally divers by recent economical growth in shipping industries, irrigation based farming, and manufacturing.[41] According to the Texas Comptroller and Texas Water Evolution Board, the Southern region's economic growth and irrigation practices have put pressure on water demands that exceed supply, and this is expected to increase with economic and demographic trends between 2010 and 2060.[41]

All of these economic practices in the region put pressure on both the quantity and quality of water in the Edwards Aquifer. A contempo study showed that salinity in groundwater wells in the aquifer is loftier, potentially affected past side by side, natural common salt deposits likewise as brine seepage from nearby oil fields.[42] Additionally, irrigated agronomics is a significant user of the Edwards Aquifer groundwater, with a diverseness of crops cultivated, including: " vegetables, hay sesame, soybeans, peanuts, cotton fiber, corn, sorghum, wheat, and oats".[43] Too, the urban center of San Antonio is located forth the eastern edge of the aquifer and was listed as the 7th largest city in the The states past population in 2014.[44]

Stakeholders [edit]

Historically, the Edwards Aquifer has served equally the sole source of h2o for the metropolis of San Antonio.[45] This viii-county metropolitan area is the second fastest-growing area in the country of Texas and depends on the aquifer for both recreational use and clean drinking water.[46] [47] San Antonio Water System (SAWS) is the largest public water utility arrangement that serves the viii counties of the San Antonio metropolitan expanse. A full of 92 water wells with a daily pumpage rate of 203.7 meg gallons supply water to SAWS' customers.[48]

In improver to the 2.iii million San Antonio residents are the communities of New Braunfels and San Marcos that depend on the aquifer for clean drinking h2o. Farming and ranching communities are other pregnant dependents of the aquifer.[48] From the 1930s to the 1980s, withdrawals accept quadrupled with over half of the current withdrawals serving municipal water purposes while the remaining goes to agricultural needs.[49] [l] More than fifty,000 people in the urban center of Austin (6% of Austin's population) rely on the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer.[38]

Five groups of stakeholders have played significant roles in shaping the use and conservation of the aquifer, including the Edwards Aquifer Authority (EAA), New Braunfels, San Marcos, San Antonio, and Texas Country University.[51] [52] Additionally, federal entities including U.s. Geological Survey, United states Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.s. Ecology Protection Agency have been involved in h2o steward activities and recovery direction plans of the Edwards aquifer system.[45] [46] [47]

The EAA was created as a result of Edwards Aquifer Authority Human activity enacted by Texas State Legislature in 1993. The main purpose of EAA is to oversee the permitting system for water withdrawals from the aquifer organization. A subdivision of country authorities, EAA is more of a liaison between federal agencies (e.thou. USFWS, USEPA, USGS), country agencies (e.g. Texas Water Development Board, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, etc.) and non-governmental organizations (e.grand. Texas H2o Conservation Clan, Texas Clan of Groundwater Districts).[45]

| Stakeholders | Involvement in aquifer resource management |

|---|---|

| Farmers and ranchers | Depend on water for crops and brute husbandry |

| Edwards Aquifer Authority | Responsible for permitting process for water withdrawal from the Edwards aquifer system |

| Metropolitan areas: Uvalde, San Antonio, New Braunfels, and San Marcos | Depend on water for drinking, recreational uses, utilities, and for irrigation |

| San Antonio Water Arrangement (SAWS) | Largest public utility system that relies on Edwards aquifer system. |

History [edit]

European colonization [edit]

Castilian missionaries who arrived in Texas in the 1700s looked to the Edwards Aquifer as their primary source of water. Springs fed by the aquifer played a key role in deciding the location of the Alamo mission and other settlements in the Texas Hill Country.[53] As Europeans continued to settle the region, and equally Texas was caused by the United States, the Edwards Aquifer continued to supply h2o for farming, ranching, and rural domestic apply.[54]

Regulation and management [edit]

In the 1950s Texas experienced the worst drought on record.[55] Legislature for protection of the Edwards aquifer began in 1959 with the cosmos of the Edwards Secret Water District, which created and supplied maps and worked with licensing departments for development interests. Starting in the 1970s, the Texas H2o Quality Board (TWQB) first recognized the aquifer and issued regulations regarding surface recharge zones. Following these showtime steps, regulations began to include the need for geologic assessments prior to evolution, blueprint standards for clandestine storage tanks and pipes, and fees for development.[56]

In 1992, the TWQB declared the Edwards aquifer an hugger-mugger river due to the precense of endangered species, but this was overturned after the same year. In 1993, Texas Senate Nib 1477 established the Edwards Aquifer Authority to manage the aquifer and to limit pumping to protect the bound menstruum levels.[57]

In 1997, Chapter 36 of the Texas Water Code was amended by Senate Pecker 1 of the 75th Texas Legislature to require all underground h2o conservation districts in Texas to develop a groundwater management plan and submit it for approving past the Texas H2o Development Board every five years on the ceremony of initial approval (September 17, 1998 for the Edwards Aquifer Authority). The initial requirements of the groundwater management plans were that they accost the efficient use of groundwater, methods of controlling and preventing waste of groundwater, conjunctive surface water bug, natural resource issues that impact the utilise and availability, of groundwater, and methods of controlling and preventing subsidence.

The requirements of groundwater management plans have since undergone expansion to require the inclusion of planning requirements for addressing drought conditions and conservation (2001, the 77th Texas Legislature Senate Bill ii), estimates of the managed bachelor groundwater, the amount of groundwater used within each commune, the amount of recharge from precipitation, projected surface water supply, total water demand inside the commune, and consideration of water management strategies that were included in the adopted country water plan (2005, 79th Texas Legislature HB 1763). Senate Bill 2 of the 77th Texas Legislature also required the groundwater conservation districts to submit groundwater management plans to the Chair of whatever Regional Water Planning Group in which any part of the commune is located and then that they may specify whatever area(s) that disharmonize with the approved Regional Water Programme[1].

In addition to the groundwater direction program, the Edwards Aquifer Authority board of directors maintains a three-year rolling strategic plan that is updated annually. The 2015-2017 strategic plan adopted on October xiv, 2014 identifies half-dozen major goals:

- Goal A: Sustain Federally Protected Aquifer-Dependent Species

- Goal B: Ensure Effective Management of the Edwards Aquifer

- Goal C: Enhance Recharge Program for Improved Aquifer Management and Springflow Maintenance,

- Goal D: Prevent the Pollution of the Aquifer

- Goal E: Conduct Research that Enhances Understanding and Effective Direction of the Aquifer

- Goal F: Develop a Diverse, Service-Oriented Organization

- Goal Yard: Build Shared Value in the EAA Mission

- Goal H: Sustain Fiscal Stability [three]

With the growth of regional cities such as San Antonio, municipal demand for water increased.[58] The second half of the twentieth century saw a loftier volume of legal activity regarding rights to the aquifer.

Water remainder [edit]

Although between 25 and 55 one thousand thousand acre-feet of water may exist present in the Edwards aquifer, but a small portion of this water is practically or legally available for use.[eleven] Storage is the departure between recharge (inputs) and discharge (outputs) from the Edwards Aquifer.

Annual storage can be negative during dry years with loftier h2o employ and positive during moisture years with relatively depression water use. A long-term negative imbalance betwixt recharge and discharge in an aquifer may lead to the depletion of the bachelor water in the aquifer.

Annual storage between 1955 and 2012 estimated from data provided by a continuing program betwixt the U.S. Geologic Survey and the Edwards Aquifer Potency ranged from -633,000 to +1,653,000 acre-feet per yr. The average storage during this menstruum was 37,000 acre-feet per yr.[three]

Water inputs, outputs, and storage to the Edwards Aquifer based on data collected by the Edwards Aquifer Authority between 1955 and 2012

Inputs (recharge) [edit]

Water mainly enters the Edwards Aquifer in two ways: it either falls as atmospheric precipitation and percolates directly into the aquifer, or it enters as streamflow flowing through the Recharge Zone. The Recharge Zone occurs forth the Balcones Fault Zone where the Edwards Plateau drops steeply and meets the Gulf Coastal Plain. Here, highly fractured limestones are exposed at the Earth's surface, which allow rain and streamflow to infiltrate directly into the aquifer.[59]

The Contributing Zone, which occurs on v,400 mi2 (14,000 km2) of the Edwards Plateau (Texas Colina State), collects precipitation and streamflow that bleed to the Recharge Zone. Major streams draining the Contributing Zone include Cibolo Creek, Helotes Creek, Barton Creek, and Onion Creek.[sixty] H2o is unable to percolate into the aquifer in the Contributing Zone because much of the underlying geology is impermeable.[61]

Average atmospheric precipitation in the region is around 30 inches per yr.[62] Only precipitation that falls on the contributing area is available for infiltration. With a contributing and recharge surface area of over half dozen,650 mi2, the hateful annual volume of precipitation that is available for recharge is x,660,000 acre-feet (13.15 cubic kilometers), or the equivalent of 5.3 one thousand thousand Olympic sized swimming pools. The boilerplate annual recharge rate betwixt 1934 and 2013 is estimated to be 699,000 acre-anxiety (median annual recharge is 556,950 acre-feet),[63] [64] or only six% of the total inputs to the system.

Outputs (discharge) [edit]

H2o from the Edwards Aquifer is discharged in two ways: information technology is either pumped from wells (well belch) or information technology leaves as stream outflow (spring discharge). The Edwards Aquifer Authorization (EAA) and the Usa Geological Survey (USGS) have monitored annual well and bound discharges since 1934.

Almanac well discharge - the sum of all well discharges in a year - ranged from 219,300 acre-feet to 542,500 acre-feet between 1955 and 2012. The average well discharge for this menstruation was approximately 371,667 acre-anxiety, equivalent to 183 thousand Olympic-sized pond pools.[3]

Annual spring discharge ranged from 69,800 acre-feet to 802,800 acre-anxiety between 1955 and 2012. The boilerplate bound discharge for this period was approximately 392,991 acre-anxiety.[3]

During dry years, more water is discharged from wells while during wet years, more water is discharged from springs. Annual total groundwater belch from pumping and springs ranged from 388,800 acre-anxiety to 1,130,000 acre-feet, and the average full groundwater discharge for 1955 to 2012 period was approximately 764,431 acre-feet.[3]

| Reported Employ (Permitted Wells) | Unreported Utilize | Subtotals | Total Discharge | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | Irrigation | Municipal | Industrial | Domestic/Livestock | Not-reporting facilities | Well | Spring | |

| Atascosa | 1,208 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,208 | 0 | i,208 |

| Bexar | 4,179 | 216,051 | 15,648 | 8,893 | 5,046 | 249,817 | 51 | 249,868 |

| Comal | 63 | five,781 | 7,061 | 390 | 0 | xiii,295 | 141,412 | 154,707 |

| Guadalupe | 0 | 69 | 167 | 0 | 0 | 236 | 0 | 236 |

| Hays | 177 | 2,341 | i,292 | 858 | 195 | 4,863 | 91,210 | 96,073 |

| Medina | 33,755 | v,911 | 2,007 | one,089 | 0 | 42,762 | 0 | 42,762 |

| Uvalde | 36,959 | 3,870 | 95 | 2,510 | 209 | 43,643 | 133 | 43,766 |

| Totals: | 76,341 | 234,023 | 26,270 | 13,740 | 5,450 | 355,824 | 232,806 | 588,630 |

Hydrologic modeling [edit]

Scientists with the United States Geologic Survey have adult numerical groundwater flow models for the San Antonio and Barton Springs aquifer segments to determine the amount of water in the aquifer, the direction it is flowing, and its velocity. These are used to estimate the sustainable levels of groundwater withdrawal throughout the aquifer.[65] Given ample data is needed for numerical simulations, still often defective,[66] regional modeling of large aquifers is difficult, just modeling segments within an aquifer is common and provides useful information for water users throughout the aquifer.

Aquifer storage is correlated with h2o levels recorded in the J-17 Bexar index well which serves as the sole official monitoring well in the Edwards Aquifer.[62] [64] The J-17 well, is located in the artisanal confined Edwards Aquifer at a location AY-68-37-203 based on the breadth and longitude.[64] Water levels have been recorded in the J-17 well since the 1910s, and is used to generalize the entire aquifer system. Changes in aquifer storage are used to estimate recharge rates.

In the Edwards aquifer, groundwater menses models have been adult for the San Antonio and Barton Springs aquifer segments in the San Antonio region of Texas. Two model simulations were conducted: steady state and transient. A steady-land groundwater flow model requires magnitude and management of flow remain constant, whereas a transient model simulation allows for a alter in water storage over time. Steady-state results advise water leaving the aquifer occurs through springs (73.3 percent), water well pumping (25.seven percent), and to the Colorado River (0.6 percent). Inflow of h2o to the aquifer mostly occurs through natural recharge (93.5 pct) and water delivered through the aquifer'south regional boundaries (six.5 percentage). The transient simulation model too suggests discharge primarily occurs through springs, followed by water well pumping; however, changes in h2o storage is heavily dependent upon the corporeality of monthly precipitation and water well pumping volumes.[67]

Policy [edit]

Edwards Aquifer Authority regulates withdrawal permits, transfers, and groundwater conservation plans under authority granted by the Texas legislature. Groundwater law in the country of Texas is governed by the Rule of Capture, which gives landowners the correct to pump groundwater below their country, with the exception of drilling a lateral well extending under a neighbour's property, wasting h2o, or pumping with the intention of causing harm to a neighbor's well.[68] In order to construct a well to withdraw water from the Edwards Aquifer, even so, a user requires a permit that is granted past the Edwards Aquifer Authority. Permits for existing users are adamant by maximum historical employ, taking into consideration the overall availability of water in the aquifer.[69]

Wells that produce less than 25,000 gallons per solar day, wells that are solely for the purpose of watering livestock, and a few other exceptions are considered exempt wells that exercise not crave a permit. Permits for withdrawal can be transferred to another user, provided that the new utilise is beneficial and occurs within the boundaries of the Authority, with a few geographical exceptions.

Groundwater conservation plans are required for permit holders who withdraw more than three acre feet per year (equivalent to 2,678 gallons per mean solar day), unless irrigators tin show more than 60 percentage efficiency in their water use. Conservation plans require the apply of Best Management Practices, as determined past the Edwards Aquifer Dominance.[seventy]

In recharge zones of the aquifer permits are required to shop regulated substances that could impairment water quality. Additionally, The Texas Committee of Environmental Quality requires special permits for structure in the recharge zones of the aquifer.[71]

Conservation Efforts [edit]

Encompassing an area of eight counties across due south-central Texas including the City of San Antonio and its surrounding communities,[72] the Edwards Aquifer is the main water supply source for the region, providing water for agricultural and industrial purposes and necessary water flow for endangered species habitat, as well as recreational purposes. As a result of a lawsuit filed by the Sierra Club under the Federal Endangered Species Deed in 1991, the Edwards Aquifer Dominance (EAA) was created to oversee the aquifer in its conservation efforts.[48]

The Texas Legislature directed the EAA to regulate pumping from the aquifer, implement critical flow direction restrictions, and pursue measures to ensure minimum continuous spring flows of the Comal and San Marcos Springs are maintained to protect endangered and threatened species to the extent required by federal law.[72] In 2013, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service canonical Edwards Aquifer Authority's Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP), which is a regional xv-yr plan designed to protect the water menstruum and species in the Edwards Aquifer region.

The HCP supports 3 major project groups of habitat protection measures, flow protection measures, and supporting measures such as practical research, ecological and biological, and water-quality monitoring. HCP project examples include minimization and mitigation of the impacts of low period, by restoring native riparian zones in order to do good the Comal Springs riffle beetle by increasing the amount functional habitat and food sources (i.east., root structures and associated biofilms).[73] The method of riparian zone establishment will include the removal of non-native, followed past the replanting of native vegetation that may exist considered representative of a salubrious, operation riparian zone.[73]

Although implementation of the HCP exists primarily within the EAA, a broad grouping of stakeholders plays a role in the management of the Edwards Aquifer. The National Research Quango (NRC) committee, formed past the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), released the offset of three scientific reports in 2015 that evaluate and make recommendations for Habitat Conservation Plan programming of the Edwards Aquifer.[72]

Legal activeness [edit]

In the by conflict existed betwixt the Sierra Club and US Federal and Land agencies, cities, and industrial water users.[74] [75] [76] The conflict is between groups that want to pump more water from the aquifer for human use and those that desire to go on water in the aquifer, to feed springs which provide habitat from endangered species.[74] This conflict tends to emerge later on periods of drought in 1988[77] and in 1995-1996[78]

In the initial lawsuit was Sierra Gild v. Babbitt in 1991.[74] The plaintiffs included environmental groups (Sierra Gild), water districts (Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority and Bexar Metropolitan H2o District), municipalities (City of San Marcos and City of New Braunfels), and utilities (Green Valley and Atascosa Rural Water Supply corporations). The defendants included, regime agencies (US Fish and Wildlife Service, State of Texas, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department), Urban center of San Antonio, and multiple industrial water users.

In Sierra Guild 5. Babbitt the plaintiffs claimed that the defendants were not fulfilling their duties under the Endangered Species Human activity, to protect endangered species and their ecosystems. The endangered species included the Fountain Darter, San Marcos Salamander, San Marcos Gambusia, Texas Bullheaded Salamander, and Texas Wild-rice. The ecosystems for these species depends on water from Comal Springs and San Marcos Springs which have the potential to run dry if too much h2o is withdrawn from Edwards Aquifer.[74]

The terminal decision sided with the Sierra Gild and other plaintiffs and in 1993 restrictions were placed on pumping from Edwards Aquifer.[74] [75] As an outcome of Sierra Club five. Babbitt as a result of this lawsuit, legislation was passed which created the Edwards Aquifer Authorisation.[72] This was also non the finish of litigation, in that location was an attempt to appeal the initial Sierra Social club v. Babbitt in 1993 Sierra Gild v. Babbitt the appeal was denied because the US Fish and Wildlife Service agreed with the original ruling, and the City of San Antonio and industrial water users were unable to bear witness that they were injured by the original Sierra Club 5. Babbitt ruling.

Due to Sierra Club v. Babbitt the Edwards Aquifer Human action 1993 was passed which created the Edwards Aquifer Potency to oversee pumping regulations.[79] In the example Barshop v. Medina Under. Wat. Cons. Dist. 1996, Medina County Nether Water Conservation District challenged the Edwards Aquifer Dominance over the constitutionality of the Edwards Aquifer Act.[80] The challenge was over whether belongings owners have the constitutional right to pump water from their land, or whether concerns for water conservation and endangered species take precedence. Barshop v. Medina Under. Wat. Cons. Dist. went to the Texas Supreme Court where the Edwards Aquifer Deed was upheld.[76] [80]

In an effort to reduce San Antonio's dependency on the solitary supply of the Edward's Aquifer, the San Antonio H2o System (SAWS) has proposed a h2o supply pipeline, the Vista Ridge, extending 82,000 ft from Burleson County to San Antonio. SAWS reports that the Vista Ridge pipeline, running 54" in diameter, will supply as much as 50,000 ac-ft of water per year for xxx years, upon the project'southward estimated completion in 2019.[81] This will increase the city's electric current h2o supply by 20%.[82]

Past 2020, SAWS estimates the average San Antonio residential water nib to be $88/mnth; this would identify San Antonio at the lowest charge per unit for water in whatsoever major Texan city. The water is provided through over 3,400 leases with private landowners drawing from the Caririzo and Simsboro aquifers. In an effort to protect the ratepayer (i.due east. San Antonio citizens), the project proposes an undetermined lifeline rate. Any h2o that fails to be delivered (i.due east. shortages, contagion) will be compensated by Blue H2o Systems, L.P and not at the expense of the ratepayer.[83]

This project is projected to promote job growth and prosperity surrounding the city, as the supply will withstand San Antonio's projected growth rate of twenty,000 people/twelvemonth.[83] Companies invested in the project lobbied for a land drought-planning nib to enable regional blessing for the sale of private activity bonds. Despite strong support from the house, the bill failed at the end of May 2015, due to lack of support in the senate. Consequently, the project requires approval from each of the 7 counties along the route.[82]

Those in favor of the Vista Ridge pipeline believe the project volition help protect and sustain the Edwards Aquifer, every bit well every bit enable the conservation of diversified water.[81] Those who oppose the pipeline are concerned that installment will damage the natural arrangement's ability to recharge the Edwards Aquifer and retain soil wet. Further, whether or not the city needs additional supply is in question, as projected increment in water demand is speculated to present commercial expansion, non San Antonio's municipal population demand. Ecology groups, such equally the Sierra Club, suggest the projection is allocating funds to an unsustainable solution, and that San Antonio should instead be "investing in culling and innovative resources that are less expensive, less energy-intensive, and locally accessible."[84]

See also [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ "The Edwards Aquifer". Environmental Science Establish. The University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 2013-01-28. Retrieved 2013-01-24 .

- ^ a b Ashworth, John (1995). "Aquifers of Texas" (PDF). Texas Water Evolution Board (Study 345).

- ^ a b c d east f Tremallo, Robin; Hamiton, Mark; Johnson, Steve; Esquilin, Roberto; Chanda, Burgoon (Dec 2014). "EDWARDS AQUIFER Authorisation HYDROLOGIC DATA Report FOR 2013". Edwards Aquifer Authority.

- ^ Eeason, Sarah. "EAA Subchapter 713 Regulated Zones". ArcGIS. ESRI. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Smith, Brian A; Darling, Bruce (2017). "Hydrogeology of the Saline Edwards Zone, Southeast Travis County, Central Texas" (PDF). Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation Commune Report of Investigations.

- ^ "Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone". Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2010. Texas Committee on Environmental Quality

- ^ "The Edwards Aquifer". San Antonio Water Organization. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2010. San Antonio Water Arrangement

- ^ "Hydrogeology of the Edwards Aquifer". www.edwardsaquifer.net . Retrieved 2015-eleven-23 .

- ^ a b Maclay, Robert W. (1995). "Geology and Hydrogeology of the Edwards Aquifer in the San Antonio Area, Texas" (PDF). Water-Resources Investigations Written report.

- ^ Rose, P. R. (1972). Edwards Group, surface and subsurface, central Texas. Austin: University of Texas Agency of Economic Geology Report of Investigations 74.

- ^ a b c Maclay, R. W., and Country. 50. F. (1988). Simulation of Flow in the Edwards Aquifer, San Antonio Region, Texas, and Refinement of Storage and Period Concepts. Washington: U.s.a. Government Press Role, US Geological Survey H2o-Supply Newspaper 2336-A.

- ^ "USGS Kentucky Water Science Center". ky.water.usgs.gov . Retrieved 2015-11-03 .

- ^ The Nature Conservancy of Texas (2008). "The Edwards Plateau Ecoregion: Extraordinary diverseness of life amid hills and canyons in Central Texas" (PDF) . Retrieved 2015.

- ^ a b c d South Fundamental Climate Scientific discipline Eye (2013). "Drought History for the Edwards Plateau of Texas" (PDF) . Retrieved 2015. ;

- ^ Eberts, S. Hydrogeologic Settings and Groundwater-Flow Simulations for Regional Investigations of the Transport of Anthropogenic and Natural Contaminants to Public-Supply Wells - Investigations Begun in 2004. (2011).

- ^ a b U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. National Chief Drinking H2o Regulations. (2009).

- ^ Bush, P. West. et al. Water quality in south-central Texas, Texas, 1996-1998. (2000).

- ^ a b c Fahlquist, L. & Ardis, A. F. Quality of water in the Trinity and Edwards aquifers, south-central Texas, 1996-1998. (2004).

- ^ Moran, M. J., Lapham, W. W., Rowe, B. L. & Zogorski, J. Southward. Occurrence and status of volatile organic compounds in ground h2o from rural, untreated, self-supplied domestic wells in the United States, 1986–99.

- ^ Long, S., Reece, B. & Eames, D. Water Resource Information Texas Water Year. (2004).

- ^ Assessment, U. E. North. C. for E. Karst Hydrology and Chemical Contamination. at <http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/cfm/recordisplay.cfm?deid=40644>

- ^ Edwards Aquifer Protection Program. at <"Archived re-create". Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2015-10-24 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as championship (link)> - ^ a b Longley, Glenn: Widemouth Blindcat from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 12 May 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- ^ Glenn Longley and Henry Karnei, Jr. (1978). Condition of Satan Eurystomus Hubbs and Bailey, the Widemouth Blindcat half-dozen. Southward.W. Tex. St. U.

- ^ a b Bexar Metropolitan Water Commune. (1999). Environmental Assessment ESA Section 10 (a)(1)(B) Incidental Have Let and Habitat Conservation Plan for Reduction of Withdrawals from the Edwards Aquifer.

- ^ Wilcox, B. P.; Owens, Thousand. K.; Knight, R. W.; Lyons, R. K. (2005). "Exercise woody plants affect streamflow on semiarid karst rangelands?". Ecological Applications. 15 (one): 127–136. doi:10.1890/04-0664.

- ^ Culver, D. C., Master, L. L., Christman, K. C., and Hobbs, H. H. (2000). "Obligate cave fauna of the 48 contiguous United states". Conservation Biology. 14 (2): 386–401. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99026.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Culver, D.C.; Christman, M.C.; Elliott, West.R.; Hobbs, H.H. Three; Reddell, J.R. (2003). "The North American obligate cave animal: regional patterns". Biodiversity and Conservation. 12 (3): 441–468. doi:ten.1023/A:1022425908017. S2CID 7275515.

- ^ Culver, D. C.; Pipan, T.; Schneider, K. (2009). "Vicariance, dispersal and scale in the aquatic subterranean fauna of karst regions". Freshwater Biological science. 54 (four): 918–929. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01856.ten.

- ^ San Marcos/Comal Recovery Team, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (1996). San Marcos and Comal Springs and Associated Aquatic Ecosystems (Revised) Recovery Programme 6

- ^ Wilson, Eastward.O. (1992). The Diversity of Life 397.

- ^

- ^ Barker, R.A.; Ardis, A.F. (1996). "Hydrogeologic Framework of the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer Arrangement, West Central Texas". U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. Professional person Paper. doi:10.3133/pp1421B.

- ^ "USGS - NAWQA - Water Quality in Due south-Central Texas - Contents". pubs.water.usgs.gov . Retrieved 2015-10-23 .

- ^ a b Ockerman, D.J. (2002). "Simulation of Runoff and Recharge and Interpretation of Constituent Loads in runoff, Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone (Outcrop)and Catchment Area, Bexar County, Texas, 1997–2000" (PDF). USGS Water-Resources Investigations Report 02–4241.

- ^ a b Office, Usa Census Bureau Public Information. "Texas Dominates List of Fastest-Growing Large Cities Since 2010 Census, Census Bureau Reports - Population - Newsroom - U.South. Census Agency". www.demography.gov . Retrieved 2015-10-24 .

- ^ "Prop ane: Edwards Aquifer Protection Plan up for renewal". KSAT. 2015-05-04. Retrieved 2015-ten-24 .

- ^ a b c GEAA. (2014). Edwards Aquifer Background Data. Retrieved Oct 13, 2015, fromhttp://world wide web.aquiferalliance.net/unique-resource/

- ^ Ashworth, J. B. (1995). Aquifers of Texas. Texas Water Evolution Board. Written report 345. Pdf: http://world wide web.cctexas.com/Assets/Departments/H2o/Files/TWDB%20Aquifer%20Report.pdf

- ^ Regional Snapshot: West Region. (2015) Texas Comptroller of Accounts. Pdf available at: http://world wide web.texasahead.org/regionalrpts/

- ^ a b Regional Snapshot: South Region. (2015) Texas Comptroller of Accounts. Pdf available at: http://world wide web.texasahead.org/regionalrpts/

- ^ Chaudhuri, Sriroop; Ale, Srinivasulu (2014). "Temporal evolution of depth-stratified groundwater salinity in municipal wells in the major aquifers in Texas, United states". Science of the Full Surround. 472: 370–380. Bibcode:2014ScTEn.472..370C. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.10.120. PMID 24295753.

- ^ Chowdhury, Manzoor Eastward.; Lacewell, Ronald D.; McCarl, Bruce A. (2011). "Result of USDA Commodity Programs on Annual Pumpage from the Edwards Aquifer". Journal of Contemporary H2o Inquiry and Teaching. 106 (1): 11.

- ^ "one 1000000 Milestone". U.South. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c FitzHugh Thomas, W.; Richter, Brian D. (2004). "Quenching Urban Thirst: Growing Cities and Their Impacts on Freshwater Ecosystems". BioScience. 54 (eight): 741–754. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0741:qutgca]ii.0.co;ii.

- ^ a b "San Antonio (city) QuickFacts from the Usa Demography Bureau". quickfacts.census.gov . Retrieved 2015-xi-05 .

- ^ a b "San Antonio H2o Organisation". www.saws.org . Retrieved 2015-11-05 .

- ^ a b c "Edwards Aquifer Authority". www.edwardsaquifer.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2015-11-05 .

- ^ Hamilton JM. 2003. Edwards Aquifer Authority Hydrogeologic Data Written report for 2002. San Antonio (TX): Edwards Aquifer Authorization.

- ^ US Fish and Wildlife Service. 1995. San Marcos and Comal Springs and Associated Aquatic Ecosystems (Revised) Recovery Programme. Albuquerque (NM): USFWS.

- ^ "Water for All. Diverse stakeholders are lauded for work to conserve Edwards Aquifer." Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine July 2014.

- ^ Ernst, C.; Gullick, R.; Nixon, Chiliad. (2004). "Conserving forests to protect water". Opflow. 30 (5): one–7. doi:10.1002/j.1551-8701.2004.tb01752.ten.

- ^ 1. Gulley, Robert 50. (2015). Heads To a higher place Water: the Within Story of the Edwards Aquifer Recovery Implementation Program. Texas A&Grand University Printing. ISBN 978-ane-62349-268-7.

- ^ 1. Rivard, Robert. "An Oral History: War and Peace Over the Edwards Aquifer". The Revard Report.

- ^ Smith, Brian; Hunt, Brian (2010). "A Comparing of the 1950s Drought of Record and the 2009 Drought, Barton Springs Segment of the Edwards Aquifer, Cardinal Texas". Central Texas: Gulf Coast Association of Geological Societies Transactions.

- ^ "Regulatory History of the Edwards Aquifer". www.tceq.land.tx.us. Archived from the original on 2015-09-18. Retrieved 2015-eleven-03 .

- ^ McCarl, Bruce A.; et al. (1999). "Limiting pumping from the Edwards Aquifer: An economic investigation of proposals, water markets, and jump catamenia guarantees". Water Resources Research. 35 (iv): 1257–1268. Bibcode:1999WRR....35.1257M. doi:x.1029/1998wr900116. hdl:10211.3/200435.

- ^ Rattan Lal, B.A. Stewart, ed. (June 19, 2012). Soil Water and Agronomic Productivity. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Printing. pp. 126–128.ISBN 978-1-4398-5080-0.

- ^ Ogden, A. Eastward., Quick, R. A., Rothermel (1986). Hydrochemistry of the Comal, Hueco, and San Marcos Springs, Edwards Aquifer, Texas. In The Balcones Escarpment, Abbott, Patrick Fifty, and Woodruff, C.M., eds. San Antonio: Geological Society of America, pp. 51-54.

- ^ Blome, Charles D., Jason R. Religion, Diana E. Pedraza, et al. (2005). USGS, U.s.a. Department of Interior, and US Geological Survey. <http://pubs.usgs.gov/sim/2005/2873/pdf/2873_Print.pdf>

- ^ "Introduction to the Edwards Aquifer". www.edwardsaquifer.cyberspace . Retrieved 2015-xi-05 .

- ^ a b Official Aquifer Level and Statistics (2015). San Antonio Water Arrangement. Retrieved 13 October 2015. <http://www.saws.org/Your_Water/aquifer/>

- ^ Edwards Aquifer Authorization (2013). Scientific Research & Reports: Hydrologic Data Reports. Retrieved 15 October 2015. <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-09. Retrieved 2015-eleven-03 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy every bit title (link)> - ^ a b c Charts and Graphs (2015). The Edwards Aquifer Website. Retrieved thirteen October 2015. <http://www.edwardsaquifer.net/charts.html#Estimated_Annual_Recharge_to_the_Edwards_Aquifer>

- ^ Bredehoeft, J. 2002. The Water Budget Myth Revisited: Why Hydrogeologist Model. Groundwater, forty (iv), 340-345.

- ^ Zhou, Y., Li, Westward. 2011. A review of regional groundwater flow modeling. Geoscience Frontiers, 2 (two), 205-214.

- ^ Lindgren, R., Dutton, A., Hovorka, S., Worthington, Due south. Painter, Due south. 2004. Conceptualization and Simulation of the Edwards Aquifer, San Antonio Region Texas. United States Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5277, 154 p.

- ^ "Texas h2o law". texaswater.tamu.edu . Retrieved 2015.

- ^ "Edwards Aquifer Say-so". www.edwardsaquifer.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-03. Retrieved 2015.

- ^ "Rules and Statutes." Edwards Aquifer Authority. Northward.p., n.d. Web. nine Oct. 2015.

- ^ "Texas Commission on Environmental Quality". Retrieved 2015.

- ^ a b c d ., National Research Quango (2015). Review of the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Program. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press. ISBN978-0-309-36887-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Habitat Protection Measures." EAHCP — Restoration of Riparian Zones and Riffle BeetleRiparian Improvement. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Oct. 2015http://world wide web.eahcp.org/index.php/habitat_protection/comal_springs/restoration_of_riparian_zones_and_riffle_beetle_riparian_improvement

- ^ a b c d e Sierra Guild v. Babbitt , MO-91-CA-069 (Due west.D. Texas 1993).

- ^ a b Sierra Club v. Babbitt , 995 F.2d 571 (Court of Appeals, 5th Excursion 1993).

- ^ a b Sierra Club v. City of San Antonio , 112 F. 3d 789 (Courtroom of Appeals, 5th Excursion 1997).

- ^ Changnon, Stanley A. (September 1989). "The 1988 Drought, Barges and Diversions". Message of the American Meteorological Society. 70 (nine): 1092–1104. Bibcode:1989BAMS...lxx.1092C. doi:ten.1175/1520-0477(1989)070<1092:tdbad>ii.0.co;2.

- ^ Halpert, Michael S.; Bell, Gerald D. (1996). "Climate Assessment for 1996". NOAA.gov. Climate Prediction Middle, NCEP/NWS/NOAA. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ Tex. Gen. Laws § 2350, ch. 626, 73rd. Leg. (1993). http://world wide web.edwardsaquifer.org/files/download/5a48e1d88ffe061

- ^ a b Barshop v. Medina Nether. Wat. Cons. Dist. , 925 Southward.W.2d 618 (Supreme Court of Texas 1996).

- ^ a b Puente, Robert. "SAWS Board of Trustees Conference; Vista Ridge Water Supply Contract" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-03-17.

- ^ a b "Vista Ridge exec discusses failed pipeline beak". San Antonio Express-News. iii June 2015. Retrieved 2015-x-24 .

- ^ a b "Vista Ridge Fact Canvass" (PDF).

- ^ "Sierra Club: San Antonio Doesn't Need Vista Ridge Pipeline". The Rivard Report. July 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-24 .

External links [edit]

- Edwards Aquifer Authority

- Handbook of Texas Online, southward.v. "EDWARDS UNDERGROUND WATER District,"

- Edwards Aquifer Home Page, Gregg Eckhardt

- Endangered Species of the Edwards Aquifer

- Save Our Springs Alliance - Edwards Aquifer Protection Plan

- Greater Edwards Aquifer Brotherhood

- Edwards Aquifer Guide Academy of Texas Library

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwards_Aquifer

0 Response to "What Is the Record High Reading for the Edwards Aquifer"

Post a Comment